Preface

I will use the collective term “Queer” in place of LGBTQIA for ease of use, despite its controversial history as a slur. I have been open about the fact that I am a part of this community, and feel comfortable using it, and also feel comfortable with cis and straight friends using it as an umbrella term. However, do know that this term was used derogatorily as a slur for many decades, and older folks many have a strong aversion to it because of that. If this is the case for others, please don’t use this term around them

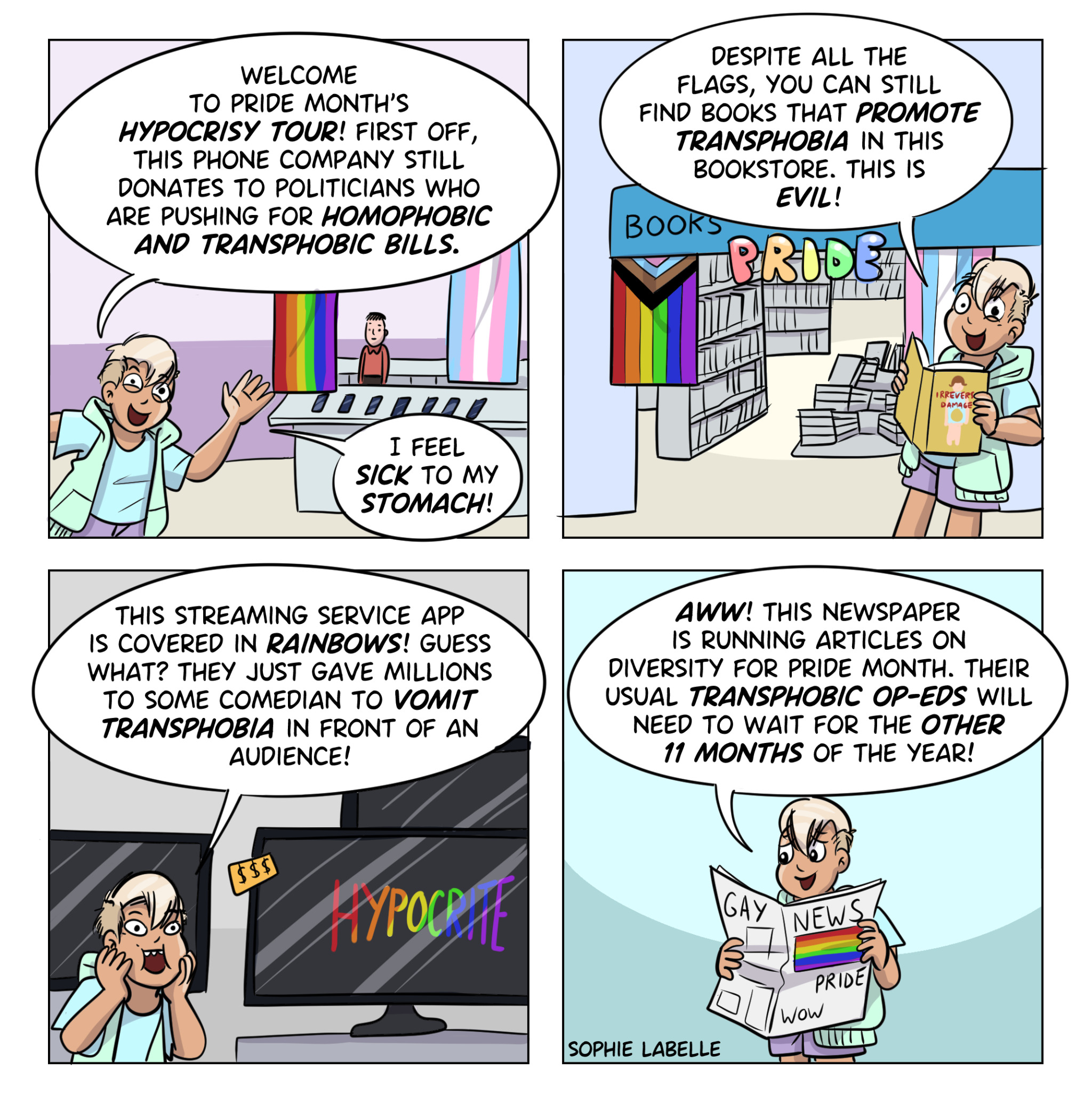

June is “Pride Month“, which is the time that folk celebrate our existence. In recent years this tradition has become so commercialized that its nauseating. Pride Month is not brought to you by T-Mobile, Disney, Spotify, or the government. Frankly to say otherwise is insulting because they have historically supported our marginalization (and often still do).

Today I want to give a very brief overview of the origin of pride month.

Background

Most of the first half of the 1900s were very inhospitable for queers. After World War 1 many queer folks took the opportunity to re-settle in larger cities, but were heavily stigmatized. During this time prohibition was kicked off, and speakeasies were reluctant to pass by any opportunity to stay in business. Because of this, many speakeasies inadvertently became queer social hangouts, since no where else would allow us to gather. However, even still, the police were eager to not only stop alcohol, but also stop us from gathering. One of the most popular queer hot spots, Eve’s Hangout, was raided and subsequently closed in 1926.

In the aftermath of the World War 2 many people wanted to regress societal norms even further. One of the people who fought against us was Senator Joseph McCarthy. He was known for branding people as enemies of the US or as security risks, despite whether his accusations were true. One of the accusations that he lobbed were being queer. His efforts helped stigmatize us on a national level and led to us being marginalized, harassed, and threatened. We were fired from our jobs, tracked by the government as if we were terrorists, raided our neighborhoods, illegalized our expression, were unable to show affection in public, unable to gather peacefully, and were deemed an illness.

There were organizations, such as the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis, which sought to fight this regression with education. They wanted to teach the general public about how queer folks are really no different than straight and cis folks. These groups also helped organize some of the earliest queer rights rallies.

Additionally, there were queer poets and authors in this time that started to speak out and let other queer people know that they weren’t alone. It became increasingly more common for queer social hotspots (aka “gay bars“) to crop up as a result. Many of these bars were owned by the mafia, and paid off the cops to prevent them from getting raided. This allowed for us queer folks to have public gathering places, but unfortunately the mafia also treated us rather poorly.

Setting the Stage in New York

New York City was to host the 1964 World’s Fair, where people from all around the world would come to gather. The mayor at the time, Robert F. Wagner Jr., saw queer folks as undesirables and was worried about the city’s public image with gay bars being allowed to exist.

Wagner ordered the liquor licenses revoked for many gay bars, and also sent in undercover cops to entrap queer people. By “entrap” I mean the cop would hit on someone of their same gender, ask them to leave together or buy the cop a drink, and arrest them for solicitation. On top of this horrific marginalization, few lawyers would defend these cases.

Thankfully the Mattachine Society was successful in getting Wagner deposed and put an end to the entrapments. However, reclaiming our social hotspots proved more difficult. There were no official laws prohibiting serving queer folks, but the courts in the State of New York permitted the practice of withholding liquor licenses to businesses it thought were “disorderly”. This essentially was a blank check for systemic discrimination against queer social outlets at the time. Bars which were known for serving queer folks lost their license and went out of business. Many businesses stopped serving us in order to keep their doors open.

The Mattachine Society staged a series of “sip-ins” in 1966 to illustrate the discrimination homosexuals faced. After a couple of failed attempts, they successfully staged their protest at the Julius, which was frequented by gay men. Three men from the Mattachine Society calmly entered and sat down in the Julius, and read from stationary, “We are homosexuals. We are orderly, we intend to remain orderly, and we are asking for service.” They were denied service.

The Mattachine society was able to successfully argue in court that the State of New York was violating queers’ First Amendment right to peacefully assemble, and this particular discriminatory practice came to an end.

The Stonewall Uprising

The Genovese crime family owned the Stonewall Inn, and in 1966 it was turned into an unlicensed bar which catered to queer folks. Unfortunately, the mafia also would blackmail high-profile patrons of gay bars, and then use extorted money to pay off the cops to prevent raids; this particular type of police bribery is known as a “Gayola“.

Despite the drinking glasses being dirty, the toilets not working, and there being no fire exits, the Stonewall was like a home to many people. It provided a place to relax, make friends, and dance (the only bar at the time that permitted this for gay men). You had to know the bouncer in order to get in in order to mitigate the chances of undercover cops coming in; this only assisted in the community knowing each other. There were two dancefloors whose walls were painted black and had colored lights shining, and places to touch up your makeup. It catered to what the queer community wanted at the time; it was the gay bar in the city.

At this time gay bars were still raided on a monthly basis. Usually the bar’s management was tipped off so they were able to deal with the cops early in the evening and then operate more-or-less normally the rest of the night. If the cops raided while people were there, they were all expected to line up and show their identification cards, and those who couldn’t or wouldn’t show them were taken to jail. Those who were dressed in drag were taken to jail. Those who were trans underwent humiliating and dehumanizing genital inspections and were then taken to jail. Cis women had to wear a minimum of 3 feminine articles of clothing or would go to jail.

On Friday, June 27, 1969 there was a rumor that there was going to be an unscheduled raid late that night / early that morning, but management waved it off since they did not receive their normal tipoff. However, sure enough, that night four undercover cops confirmed that the bar was operating, and an additional six cops raided Stonewall. About 200 people were in Stonewall at the time.

That night, the trans women refused to comply with the humiliating genital inspections. Men refused to show their identification. We had had enough. Police were sexually assaulting queer women as they were being arrested. More cop cars were coming. Some people were released and permitted to leave, but tonight instead of quickly going home, folks stayed by the Stonewall. Within minutes there were hundreds of people outside of the Stonewall, many of whom weren’t in Stonewall during the raid. The police tried to disperse the crowd, but they were met with mocking imitations.

Things continued to escalate. Rumors started flying that patrons of Stonewall were being beaten inside, and those outside began to be physically assaulted by police. The protestors started throwing debris at the cops. Stormé DeLarverie then called for the people to fight against the oppression and injustice that was being played out in front of them.

(Jackie Harmona is the blond on the left)

The crowd began to fight back. The cops were so pre-occupied with the uprising that they weren’t attending to the arrested folks, and many were able to escape. The crowd slashed the cops’ tires and tried to turn their cars over. The crowd declared that the cops raided the Stonewall because the mafia hadn’t given them their gayola, and they were being punished for it; they were pawns who refused to play their game any more. The crowd began throwing pennies at the cops to “buy them off” and show how corrupt they are. Beer cans, coins, and now garbage cans and bricks from a nearby construction site were thrown at the oppressors.

The cops ended up cowardly barricading themselves in the Stonewall. While we can’t know for sure it was them, in the aftermath of the uprising everything in Stonewall – pay phones, toilets, mirrors, jukeboxes, and cigarette machines – were all destroyed. Stonewall was destroyed. The Tactical Patrol Force (TPF) of the New York City Police Department arrived to help the cops escape, but the TPF was unprepared. Queer Rights advocate Bob Kohler recounted this scene by saying:

“I had been in enough riots to know the fun was over… The cops were totally humiliated. This never, ever happened. They were angrier than I guess they had ever been, because everybody else had rioted… but the fairies were not supposed to riot… no group had ever forced cops to retreat before, so the anger was just enormous. I mean, they wanted to kill.”

The cops tried to detain people, and chiefly targeted transwomen. However, these brave women fought their oppressors.

Eventually the TPF tried to just clear the streets, but were met with screams of “Gay power!” and mocking kicklines which sang the following to the tune of “Ta-ra-ra Boom-De-ay“:

“We are the Stonewall girls

We wear our hair in curls

We don’t wear underwear

We show our pubic hair”

The cops didn’t take kindly to this protest, and started beating people with their nightsticks. However, the crowd vastly outnumbered the police presence, and so the cops were chased around.

The uprising finally subsided around 4AM on June 28, but many people were still in the streets. The people there understood the significance of the uprising that had just taken place. They all saw that there were many queer people, that they could physically fight for their right to exist if need be, and that many of their straight and cis-gender friends would join the cause. Things would never be the same for the queer community again.

The morning papers covered the uprising, but rumors still swirled about who was doing it and what their motive was. Hundreds of people flocked to Stonewall to see it burned and graffitied with phrases like “Drag power”, “They invaded our rights”, “Support gay power” and “Legalize gay bars”, along with accusations of police looting.

Stonewall opened for business again that evening (June 28th, 1969) and the street was so crowded that it overflowed into other blocks. The energy and sentiment was very similar, and the uprising continued in a rather similar fashion, but it also drew more queers, allies, and spectators. The crowds harassed folks in busses and cars until they admitted they were gay or expressed support for the demonstrators.

This second night there were over a hundred cops there, and significant pushback against them. Those leading the charge this night, as well as the night before, were chiefly transgender women. There were three who were known as the vanguards during the whole uprising: Marsha P. Johnson, Zazu Nova, and Jackie Harmona, and this second day was no exception for their activism. On this second night, Marsha climbed up a lamppost with a heavy bag and dropped it on the hood of a cop car and shattered the windshield. While there were dozens of cops there, the crowd was still too large and invigorated for the cops to handle, and the TPF were called in again. The night raged on till 4AM in a similar fashion as the night before.

The Winds of Change

The Mattachine Society always advocated for a mild and moderate approach to activism, in order to appeal to the sensibilities of their oppressors. However, Stonewall represented a drastic shift in approach; it was one that felt organic and powerful. Many, especially after Stonewall, became disillusioned with the mild approach.

Mattachine tried to find a balance between the two approaches, but ultimately a new group called “The Gay Liberation Front” was formed which had a more radical approach to activism. However, this passion seemed to also be a stumbling block for the GLF; the group was unable to form a cohesive approach to activism, and all of the meetings were chaotic. Not long after it was formed it was disbanded. The successor group, “Gay Activists Alliance” was far more organized and effective. The GAA developed a political tactic that they called “Zapping“, which was essentially ambushing political figures in public and in press conferences to catch them off guard and force them to acknowledge queer rights.

On November 2, 1969, Craig Rodwell, his partner Fred Sargeant, Ellen Broidy, and Linda Rhodes proposed the following at the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations (ERCHO) meeting in Philadelphia:

“We propose that a demonstration be held annually on the last Saturday in June in New York City to commemorate the 1969 spontaneous demonstrations on Christopher Street and this demonstration be called CHRISTOPHER STREET LIBERATION DAY. No dress or age regulations shall be made for this demonstration.

We also propose that we contact Homophile organizations throughout the country and suggest that they hold parallel demonstrations on that day. We propose a nationwide show of support.”

All the groups there voted in favor of the march except the Mattachine Society, which abstained.

The group started planning and fundraising for the march in January 1970, and it became a large cultural co-operation to make it happen. Businesses, individuals, and families all got involved to make this march happen. Chief among these organizers was Brenda “Mother of Pride” Howard. Brenda went even further than a single march and envisioned a week-long celebration. Brenda, Stephen “Donny the Punk” Donaldson, and L. Craig Schoonmaker are credited for popularizing the term “Pride” for this celebration.

When June 28th, 1970 came along, which was the first anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, queers marched with banners and signs through the streets of New York. The march was scheduled to take twice as long as it did, but everyone was so excited that it ended rather quickly. However, this march became a yearly tradition not only in New York City, but around the world for queers everywhere. Brenda’s vision expanded even further, and we now celebrate Pride the entire month of June.

Conclusion

We queers decided we had had enough on June 28th, 1969. On this day we battled our oppressors, and won. This victory forever changed how we thought of ourselves and we strived to claim our rightful place in society. We celebrate this victory every June by marching and proudly announcing our existence and supporting other queer folks.